Posted March 17, 2022 at 10:37am by Anonymous (not verified)

The Next Generation of Vermont Farmers

Young Farmers in Vermont Met with Challenges and Opportunities

By Shane Rogers, Farm to Plate Communications Manager at the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund

The landscape of farming is changing throughout the country, and Vermont agriculture is by no means an exception. To see this borne out, one only has to look to the dairy industry which has shaped Vermont’s identity and working landscape over the past generations. The idyllic image of Holstein cows, red barns, and big round bales of hay now lay in stark contrast to the hard realities dairy farmers have found themselves in as milk prices continue to remain depressed year-after-year. However, these price pressures are not just limited to the dairy industry, they’re affecting the whole sector and, to boot, many of the farmers who are navigating these shifting landscapes are getting older, nearing retirement age and are in need of a new generation to succeed them.

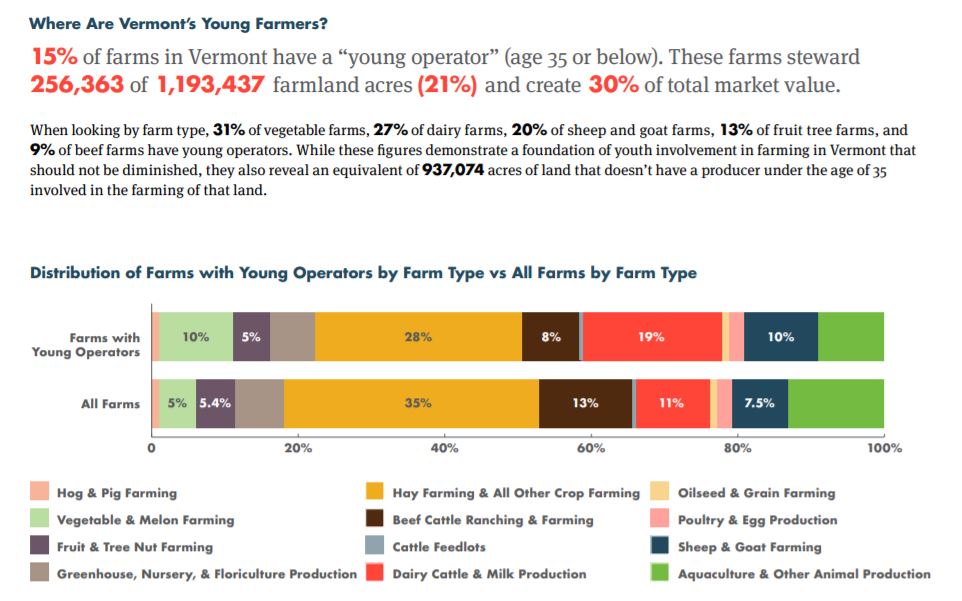

As it stands right now, 15 percent of the 6,808 farms in Vermont have a “young operator” – age 35 or below – working on the farm. These farms steward 256,363 of the 1,193,437 farmland acres in the state and are responsible for 30 percent of the $781 million total market value that agriculture creates in Vermont. While the contributions of young farmers are not insignificant, there still remains 937,074 acres of land that don’t have a young operator involved in the farming of that land, with over 15 percent of those farmers being 75 years old or older. Click here to read more in the Farm to Plate Annual Report.

Is farming even still a viable career for a young person?

With only one quick look at Instagram or a brief scan of the pretty posters of farmers in the field lining the supermarket shelves, it may be easy for young people to be swept up in the romance of farming – lush greens, hands in the dirt, determined but joyous smiles, the whole nine yards (or acres if you prefer). But, the stark reality is that it’s hard work, things break, the weather doesn’t cooperate, especially with the effects of climate change becoming more noticeable with the onset of extreme weather events, and margins are almost unbearably thin. Add in the burden of student loans, skyrocketing healthcare costs, childcare considerations, and much more that millennial and Gen Z generations are facing in a pronounced way, and the answer, on paper at least, is teetering towards “no.” But for many young folks and organizations in Vermont, that simply isn’t the case. Whether it’s for the love of the land and working outdoors, an affinity for animals and plants, or a belief in creating a food system that works for everyone, they’re dedicating their careers and lives to making farming work in Vermont among the ever-changing landscape of our food system.

Taylor Mendell, 32, and her husband Jacob, 31, who own Footprint Farm in Starksboro are two of those young operators who are making a go of it in this shifting Vermont agriculture landscape. The farm, which sits on 2.5 acres of usable cropland of which 1.75 acres are in production, was started in 2013 with another partner. Now as the sole owners, Taylor and Jake, who met in California and moved back east to take over land that was originally owned by Jake’s parents, have built the operation up and, for all intents and purposes, are considered a success story in the world of farming. However, Taylor is the first to admit that farming is hard work and being successful doesn’t actually always feel like success.

“I think the part that is hard for me to reconcile with is, yes, we are, according to a lot of people, a success story,” says Mendell. “However, it still feels too hard. It feels too stressful and too volatile. I feel like I should get another job just in case.”

Taylor is not afraid to share these concerns with the farm’s ever-growing social media audiences, through her new venture, Habit Farming, or with the farmers and advocates that are part of the Vermont chapter of the Young Farmers Coalition of which she is president. It’s her way of working to build a community around the trials and errors that come with owning and operating a small diversified farm in this changing landscape. She is building a support system and letting folks know that they are not alone even when it feels like this business and lifestyle can be next to impossible.

“I think it should be possible,” she says. “And if we have the privileges that allow us to farm and be comfortable enough farming [and] we can somehow help make it possible to keep people in agriculture […], the Vermont style of agriculture, then I think we should keep doing it, it seems like a worthwhile life to live.”

One of the things that makes Taylor and Jake a success, even in the face of adversity, is that they have settled into a business model that works for them and their operation. As of now, their market stream is split into thirds focusing on CSAs, farmers markets, and wholesale production. While it may have taken a few years to iron out the details, part of their comfort moving forward stems from the positive feedback they receive from technical assistance providers that they’re able to access for free through various programs in Vermont.

“Having an expert tell me that I was doing well has really changed my perspective on things, rather than me being like ‘I don’t know, it doesn’t feel good so we’re probably not doing well,’” says Taylor.

Young farmers call in the experts

Taylor and Jake are not alone in tapping into this type of technical assistance in Vermont. Folks like Sam Smith, a farm business specialist with the Intervale Center in Burlington who has worked with Footprint Farm and many others, provide farmers with help in business planning, transfer planning, enterprise development, and cash flow analysis. Part of the job also involves not pulling any punches.

“I would say if you really love farming but you don’t want to be a business person, grow on a homestead scale and go get a day job,” says Smith. “We jokingly refer to ourselves as the dream crushers, but it’s really not a joke,” he adds later with a chuckle.

Smith, who is part of a team of three other business specialists at the Intervale Center, has been in the position for six years and holds a Masters in Business Administration. Coming to the position circuitously, he has also worked as a farmer and a social worker prior to joining the Intervale. To Smith, his job, whether it’s for new and beginning farmers or old hands of the trade, is to identify viable entrepreneurship in the agriculture sector and help that to flourish. And when it comes to doing that, while he appreciates folk’s principles for getting into growing food in the first place, he takes a very practical approach to it all.

“It’s like, that’s your market and if you’re going to grow you have to grow for that,” says Smith. “Then educate [people] and hopefully pick up customers that you wouldn’t normally get.”

Hurdles remain for young farmers

While organizations like the Intervale Center, and the technical assistance they provide, are invaluable for farmers there still remain many issues, especially for a young person, that pose big hurdles to pursuing the ownership and operation of a farm as a career. These issues can range from an increase in land pressure for non-agriculture use that drives up prices and threatens the very working landscape that Vermont has built its brand around; to an aging Vermont farming population that are remiss to see their farms run in different ways; or such other things like student debt, healthcare, retirement savings, and housing concerns.

Jake Kornfeld, farm production coordinator at The Farm at Vermont Youth Conservation Corps in Richmond. Photo courtesy of VYCC.

Jake Kornfeld, farm production coordinator at The Farm at Vermont Youth Conservation Corps in Richmond. Photo courtesy of VYCC.

For Jake Kornfeld, 25, these considerations are partly what led him to his current position as the farm production coordinator at The Farm at Vermont Youth Conservation Corps in Richmond. In the summer, he trains AmeriCorps members in farming while managing the day-to-day farm operations which produces food for VYCC’s Health Care Share, a food donation program providing food-insecure families with fresh food and nutrition education to about 400 families through their health care provider. In the winter, he splits his days doing planning and administrative work in the mornings and spending his afternoon fixing odds and ends around the farm. Most notably, he is getting to do the work that he loves while also taking home a salary and benefits. This something that isn’t always afforded to those farmers who strike out on their own, a fact that can be a huge deterrent to young people who may be interested in the career.

“I want to run the farm as best as I can,” says Kornfeld. “But it helps you sleep at night to know that if a cooler breaks you’re not going to lose your income for the year and that’s an incredible thing as a farmer, to be able to have income guaranteed.”

For Kornfeld, who started at age 11 “shoveling cow crap” at a large dairy farm in Vermont and says he knows the systems of eight farms around the country, the nonprofit farming model followed by The Farm at VYCC not only gives him the peace of mind financially but, in turn, also gives him an opportunity to focus on issues like youth development and training future farmers, something he is passionate about but wouldn’t necessarily have time for otherwise. Since his position isn’t tied to a production quota, it gives him the flexibility to take the time to prioritize the experience of the AmeriCorps members that are part of his team each summer over the production of vegetables.

“We want to find a balance between [teaching and growing], that’s always what we’re trying to look for,” he says. “But if there’s a time when it’s a busy day and someone asks me a question, I can stop and answer it.”

Help for aspiring farmers to build the skills to succeed

For young people who want to get into farming, especially those coming with backgrounds not steeped in agricultural, the skill set needed for the career can sometimes be difficult to grow. While working on a farm is certainly the most direct way to start building a resume in that regard, pay can be low, the work is mostly seasonal, and with the general hustle and bustle of the farm it’s difficult for farmer-owners to find time to explain the decisions they’re making to their staff.

“You can go work on a farm and you’re going to learn how to harvest and weed and you’re going to do things like get up on a tractor or you’ll go do deliveries, but you’re not going to understand why everything is done or how everything is done behind the scenes,” says S’ra DeSantis, co-director and instructor for the University of Vermont Farmer Training Program.

It’s initiatives such as the UVM Farmer Training Program that are able to fill in some of that gap. As a six-month, intensive hands-on program for aspiring farmers and food system advocates, the UVM Farmer Training Program is working to teach people the steps to take agriculture operations from seed to market. The 20 to 25 person yearly cohorts, which include people as young as 19-years-old, spend about 70 percent of their time in the field getting their hands dirty, and the other 30 percent in the classroom learning about soil fertility, pest and disease management, farm financials, and business planning, with a little bit of food justice sprinkled in. The program aims to give participants a comprehensive understanding of what it takes to run a successful agriculture operation while building a network for aspiring farmers to lean on. And, while the program definitely doesn’t cover everything, DeSantis hopes that, at the very least, people walk away knowing what questions to ask as they continue on their career path.

Opportunities for the next generation of farmers

As the next generation of farmers prepares to step into the shoes of generation’s past, there are plenty of issues that still need to be resolved in order to preserve the working landscape and ensure agriculture remains a viable industry in Vermont. However, when it comes to answering if farming can still be considered a viable career for young people in the state there appears to be hope on the horizon. Whether that involves following the recommendations laid out in the Vermont Agriculture and Food System Plan: 2020 such as expanding financial support for Vermont Land Trust’s land conservation and transition efforts like the Farmland Access Program, working with public and private entities to create a financing mechanism for young farmers with no collateral, or implementing college loan forgiveness programs for aspiring farmers; it’s clear that young farmers and those helping them, are coming up with creative ways to access land, stay healthy, and, most importantly, build the skills necessary to grow food.

“I think it’s going to be challenging,” says DeSantis. “But I think there’s also opportunity.”

About Farm to Plate

Farm to Plate is Vermont’s statewide food system plan implemented by 350+ member organizations of the Farm to Plate Network to meet the goals of legislation passed in 2009 calling for increased economic development and jobs in the farm and food sector and improved access to healthy local food for all Vermonters. Vermont’s farm to plate food system plan is the most comprehensive in the country and the only state that has complete government engagement. In 2019, Vermont Farm to Plate was reauthorized beyond 2020. Governor Phil Scott signed into law H.275 – an act relating to the Farm-to-Plate Investment Program. The program is managed by the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, a non-profit organization based in Montpelier, Vermont. www.VTFarmtoPlate.com