The market for beef labelled “grass-fed” has been growing quickly across the nation, from $17 million in 2012 sales to $272 million in 2016 sales. Adding value through a production system and/or marketing label can bring higher prices paid to the farmer, and potentially higher farm profitability overall. That said, with increased demand comes increased national and international competition as well as a heightened need to improve Vermont beef genetics and grazing management in order to create year-round quality and consistency for local and regional wholesale markets. Beef represents an exciting opportunity for young and aging farmers, whether animals are grass- or grain-finished in Vermont or sold live into larger regional outlets, but will require focused coordination in order to grow within regional markets and maximize profitability and the benefits to Vermont’s farm economy.

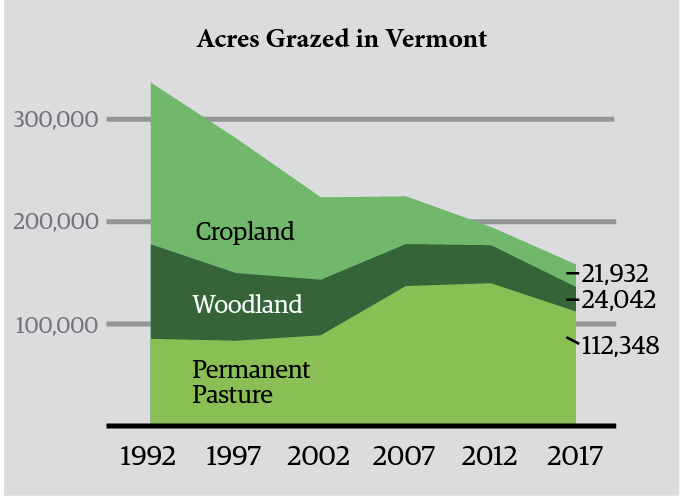

Grass-fed beef is experiencing a rising demand from consumers regionally, nationally, and internationally. Vermont is well positioned to serve grass-fed beef market demand in the Northeast, as we are able to grow grass at times of the year when other parts of the country experience drier conditions due to climate change-induced droughts, and because additional acreage could be converted from corn and hay that had been serving the dairy industry into grassland for beef production.

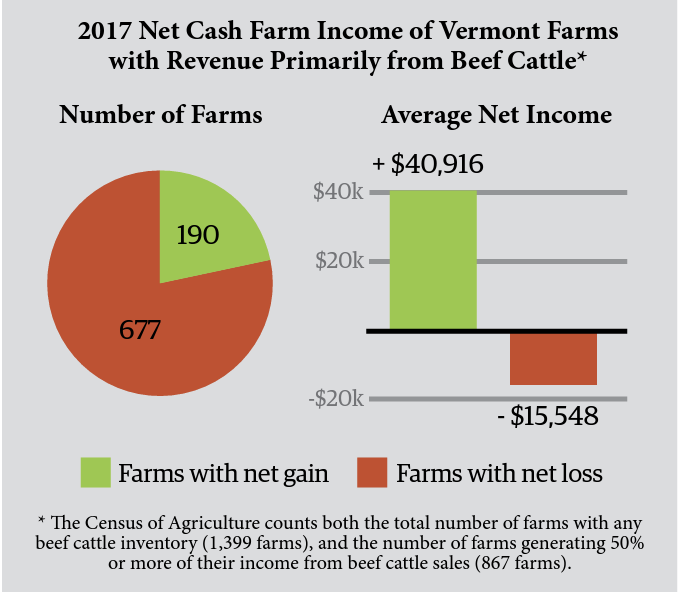

In 2017, Vermont had 1,399 beef cattle farms with more than 15,000 animals, a 37% increase over 2012. When managed well, grass-based beef and other livestock farms have been shown to increase soil fertility, improve water quality, sequester carbon, encourage biodiversity of soil microbes and wildlife, encourage farm profitability and farmer quality of life, produce high-quality meat with increased beneficial nutrients, and preserve a working landscape that enhances Vermont’s visual attraction to visitors and residents.

While offering the above benefits, the way that grass-based beef has historically been produced has been challenging financially for producers. Vermont beef farms often manage a complete birth-to-death cycle, raising animals through one or two winters, which requires expensive winter feed (i.e., hay) that deeply affects profitability. Slaughter and processing plants are financially strained by the seasonality of demand for their services. Additionally, the limited availability of less-expensive cattle feed (such as grass), genetic variability, speed of weight gain, and wide differences in grazing management skills can cause inconsistent quality in the meat eating experience.